Effects of different types of acute exercise on working memory among sedentary college students

-

摘要:

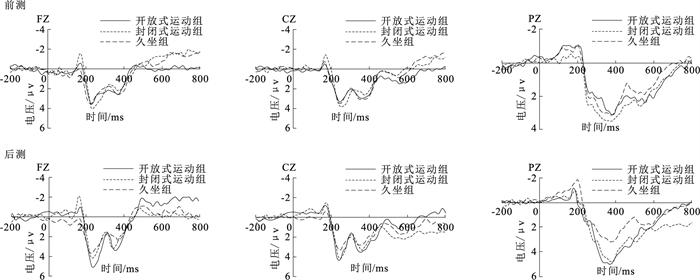

目的 探讨不同类型急性运动对久坐大学生工作记忆的影响, 为开展运动干预提供依据。 方法 2023年4月15日-5月30日, 在北京某大学招募42名久坐大学生, 采用单盲完全随机分组实验设计, 随机分为开放式运动组、封闭式运动组和对照组, 每组14人。开放式运动组进行30 min羽毛球运动, 封闭式运动组进行30 min跑步运动, 对照组静坐30 min。所有受试者在干预前后完成工作记忆2-back任务, 并记录脑电数据。对实验前后测得的行为学和脑电数据进行重复测量方差分析。 结果 开放式运动组、封闭式运动组和对照组的正确率时间主效应(0.90±0.06, 0.94±0.05;0.88±0.05, 0.94±0.05;0.85±0.10, 0.90±0.06)差异有统计学意义(F=37.14, P<0.01);反应时的时间主效应、组别与时间交互效应[(923.65±145.08, 711.56±140.93;909.59±180.28, 807.85±169.66;917.05±166.35, 871.86±186.07)ms]差异均有统计学意义(F值分别为70.55, 11.83, P值均<0.01)。采用重复测量方差分析干预前后结果显示, 3组正确率和反应时均优于前测, 组间正确率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);开放式运动组的反应时快于对照组(P<0.05), 封闭式运动组与对照组差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。P2波幅的时间主效应和时间与组别交互效应有统计学意义(F值分别为10.60, 7.66, P值均<0.01), 开放式运动组的P2波幅高于对照组(P<0.05), 而封闭式运动组与对照组差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);N2波幅仅在时间主效应上有统计学意义(F=5.94, P<0.05);P3波幅的时间和电极点主效应及组别与时间交互效应均有统计学意义(F值分别为23.16, 4.53, 5.85, P值均<0.05), 两个运动组P3波幅高于对照组(P值均<0.05), 两运动组之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。 结论 开放式运动对久坐大学生工作记忆的改善效果优于封闭式运动。 Abstract:Objective To explore the effects of different types of acute exercise on the working memory of sedentary college students, so as to provide a basis for exercise intervention. Methods From April 15 to May 30, 2023, a total of 42 sedentary college students were recruited from one university in Beijing. Using a single-blind, completely randomized experimental design, participants were randomly assigned to an open-skill exercise group, a closed-skill exercise group, or a control group, with 14 participants in each group. The open-skill exercise group engaged in 30 minutes of badminton, the closed-skill exercise group performed 30 minutes of running, and the control group remained seated for 30 minutes. All participants completed a 2-back working memory task and had their electroencephalogram (EEG) data recorded before and after the intervention. Results The accuracy rates of the open-skill exercise group, closed-skill exercise group, and control group (0.90±0.06, 0.94±0.05; 0.88±0.05, 0.94±0.05; 0.85±0.10, 0.90±0.06) showed a significant main effect of time (F=37.14, P < 0.01). Reaction times [(923.65±145.08, 711.56±140.93; 909.59±180.28, 807.85±169.66; 917.05±166.35, 871.86±186.07)ms] showed both a significant main effect of time and a significant interaction between group and time (F=70.55, 11.83, P < 0.01). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed that all three groups improved in accuracy and reaction time compared to pre-test values, with no significant difference in accuracy between groups. However, the reaction time of the open-skill exercise group was significantly faster than that of the control group (P < 0.05), while there was no significant difference between the closed-skill exercise group and the control group (P > 0.05). For EEG data, the P2 amplitude showed a significant main effect of time and a significant interaction between groups and time (F=10.60, 7.66, P < 0.01), with the open-skill exercise group exhibiting a higher P2 amplitude than the control group (P < 0.05), while the closed-skill exercise group showed no significant difference compared to the control group (P > 0.05). The N2 amplitude showed a significant main effect of time (F=5.94, P < 0.05). The P3 amplitude showed significant main effects of time and electrode position, as well as a significant interaction between groups and time (F=23.16, 4.53, 5.85, P < 0.05), with both exercise groups exhibiting higher P3 amplitudes than the control group (P < 0.05), but no significant difference between the two exercise groups (P > 0.05). Conclusion Open-skill exercise is more effective than closed-skill exercise in improving the working memory of sedentary college students. -

Key words:

- Motor activity /

- Sedentary lifestyle /

- Work /

- Memory /

- Intervention studies /

- Students

1) 利益冲突声明 所有作者声明无利益冲突。 -

表 1 不同组别久坐大学生干预前后空间2-back任务正确率与反应时(x±s)

Table 1. The accuracy and reaction time of the space 2-back task before and after intervention in different groups of sedentary college students(x±s)

组别 人数 正确率 反应时/ms 干预前 干预后 干预前 干预后 开放式运动组 14 0.90±0.06 0.94±0.05 923.65±145.08 711.56±140.93 封闭式运动组 14 0.88±0.05 0.94±0.05 909.59±180.28 807.85±169.66 对照组 14 0.85±0.10 0.90±0.06 917.05±166.35 871.86±186.07 表 2 不同组别久坐大学生干预前后空间2-back任务ERP结果(x±s,μv)

Table 2. ERP results of the space 2-back task before and after intervention in different groups of sedentary college students(x±s, μv)

组别 干预前后 人数 P2 N2 P3 FZ CZ FZ CZ FZ CZ PZ 开放式运动组 前测 14 3.61±2.68 3.28±2.54 2.14±1.45 2.03±1.75 2.37±2.42 2.87±2.14 3.19±1.92 后测 14 5.17±2.41 4.31±2.50 1.69±1.96 1.47±1.50 3.21±2.76 3.57±2.24 5.05±2.27 封闭式运动组 前测 14 4.03±2.80 3.86±1.95 1.72±3.56 2.23±3.01 2.26±2.04 2.51±2.21 3.53±1.74 后测 14 4.25±2.78 4.27±2.22 1.32±2.91 1.65±2.04 3.14±1.90 3.31±1.77 4.88±2.12 对照组 前测 14 3.50±2.12 3.34±1.97 1.81±2.63 2.02±2.43 2.37±2.19 2.94±2.25 3.22±2.16 后测 14 3.27±1.74 3.30±1.92 1.77±1.73 1.96±1.69 2.25±2.32 2.97±1.86 3.29±1.67 -

[1] PELLETIER J E, LYTLE L A, LASKA M N. Stress, health risk behaviors, and weight status among community college students[J]. Health Educ Behav, 2016, 43(2): 139-144. doi: 10.1177/1090198115598983 [2] JIANG L, CAO Y, NI S, et al. Association of sedentary behavior with anxiety, depression, and suicide ideation in college students[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2020, 11: 566098. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.566098 [3] OWEN N, HEALY G N, MATTHEWS C E, et al. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior[J]. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 2010, 38(3): 105-113. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2 [4] FORD E S, CASPERSEN C J. Sedentary behaviour and cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2012, 41(5): 1338-1353. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys078 [5] KATZMARZYK P T, POWELL K E, JAKICIC J M, et al. Sedentary behavior and health: update from the 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory committee[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2019, 51(6): 1227-1241. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001935 [6] PATTERSON R, MCNAMARA E, TAINIO M, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response Meta-analysis[J]. Europ J Epidemiol, 2018, 33(9): 811-829. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1 [7] HAMER M, STAMATAKIS E. Prospective study of sedentary behavior, risk of depression, and cognitive impairment[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2014, 46(4): 718-723. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000156 [8] FALCK R S, DAVIS J C, LIU-AMBROSE T. What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2017, 51(10): 800-811. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095551 [9] BADDELEY A. Working memory: looking back and looking forward[J]. Nature Rev Neurosci, 2003, 4(10): 829-839. doi: 10.1038/nrn1201 [10] HOANG T D, REIS J, ZHU N, et al. Effect of early adult patterns of physical activity and television viewing on midlife cognitive function[J]. JAMA Psychiatry, 2016, 73(1): 73-79. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2468 [11] TAMMELIN T. Early childhood sedentary behavior associated with worse working memory[J]. J Pediatr, 2018, 192: 266-269. http://www.xueshufan.com/publication/2773095911 [12] LÓPEZ-VICENTE M, GARCIA-AYMERICH J, TORRENT-PALLICER J, et al. Are early physical activity and sedentary behaviors related to working memory at 7 and 14 years of age?[J]. J Pediatr, 2017, 188: 35-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.079 [13] WU C H, KARAGEORGHIS C I, WANG C C, et al. Effects of acute aerobic and resistance exercise on executive function: an ERP study[J]. J Sci Med Sport, 2019, 22(12): 1367-1372. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.07.009 [14] ZHENG K, DENG Z, QIAN J, et al. Changes in working memory performance and cortical activity during acute aerobic exercise in young adults[J]. Front Behav Neurosci, 2022, 16: 884490. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.884490 [15] HUANG T Y, CHEN F T, LI R H, et al. Effects of acute resistance exercise on executive function: a systematic review of the moderating role of intensity and executive function domain[J]. Sports Med Open, 2022, 8(1): 141. doi: 10.1186/s40798-022-00527-7 [16] MARCHANT D, HAMPSON S, FINNIGAN L, et al. The effects of acute moderate and high intensity exercise on memory[J]. Front Psychol, 2020, 11: 1716. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01716 [17] YAMAZAKI Y, SATO D, YAMASHIRO K, et al. Inter-individual differences in exercise-induced spatial working memory improvement: a near-infrared spectroscopy study[J]. Adv Expe Med Biol, 2017, 977: 81-88. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28685431 [18] WHEELER M J, GREEN D J, ELLIS K A, et al. Distinct effects of acute exercise and breaks in sitting on working memory and executive function in older adults: a three-arm, randomised cross-over trial to evaluate the effects of exercise with and without breaks in sitting on cognition[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2020, 54(13): 776-781. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100168 [19] KAMIJO K, ABE R. Aftereffects of cognitively demanding acute aerobic exercise on working memory[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2019, 51(1): 153-159. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001763 [20] FENG X, ZHANG Z, JIN T, et al. Effects of open and closed skill exercise interventions on executive function in typical children: a Meta-analysis[J]. BMC Psychol, 2023, 11(1): 420. doi: 10.1186/s40359-023-01317-w [21] QIU C, ZHAI Q, CHEN S. Effects of practicing closed- vs. open-skill exercises on executive functions in individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a Meta-analysis and systematic review[J]. Behav Sci (Basel, Switzerland), 2024, 14(6): 499. http://www.mdpi.com/2829188 [22] CANTRELLE J, BURNETT G, LOPRINZI P D. Acute exercise on memory function: open vs. closed skilled exercise[J]. Health Promot Perspect, 2020, 10(2): 123-128. http://doc.paperpass.com/foreign/rgArti2020241593721.html [23] LI Q, ZHAO Y, WANG Y, et al. Comparative effectiveness of open and closed skill exercises on cognitive function in young adults: a fNIRS study[J]. Sci Rep, 2024, 14(1): 21007. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70614-0 [24] HSIEH S S, FUNG D, TSAI H, et al. Differences in working memory as a function of physical activity in children[J]. Neuropsychology, 2018, 32(7): 797-808. doi: 10.1037/neu0000473 [25] LI W, GUO Z, JONES J A, et al. Training of working memory impacts neural processing of vocal pitch regulation[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 16562. http://www.nature.com/articles/srep16562.pdf [26] DUFF K, CALLISTER C, DENNETT K, et al. Practice effects: a unique cognitive variable[J]. Clinic Neuropsychol, 2012, 26(7): 1117-1127. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/23020261 [27] CHEN A G, ZHU L N, YAN J, et al. Neural basis of working memory enhancement after acute aerobic exercise: fmri study of preadolescent children[J]. Front Psychol, 2016, 7: 1804. http://www.onacademic.com/detail/journal_1000040534794310_ef5b.html [28] ALY M, KOJIMA H. Acute moderate-intensity exercise generally enhances neural resources related to perceptual and cognitive processes: a randomized controlled ERP study[J]. Ment Health Phys Activ, 2020, 19: 100363. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100363 [29] MCMORRIS T, SPROULE J, TURNER A, et al. Acute, intermediate intensity exercise, and speed and accuracy in working memory tasks: a Meta-analytical comparison of effects[J]. Physiol Behav, 2011, 102(3): 421-428. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21163278 [30] FINNIGAN S, O'CONNELL R G, CUMMINS T D R, et al. ERP measures indicate both attention and working memory encoding decrements in aging[J]. Psychophysiology, 2011, 48(5): 601-611. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01128.x [31] ZHOU F, QIN C. Acute moderate-intensity exercise generally enhances attentional resources related to perceptual processing[J]. Front Psychol, 2019, 10: 2547. http://www.xueshufan.com/publication/2989343657 [32] IMBIR K, SPUSTEK T, BERNATOWICZ G, et al. Two aspects of activation: arousal and subjective significance-behavioral and event-related potential correlates investigated by means of a modified emotional stroop task[J]. Front Human Neurosci, 2017, 11: 608. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kamil_Imbir/publication/321748032_Two_Aspects_of_Activation_Arousal_and_Subjective_Significance-Behavioral_and_Event-Related_Potential_Correlates_Investigated_by_Means_of_a_Modified_Emotional_Stroop_Task/links/5a2f9d4e4585155b617a4fb6/Two-Aspects-of-Activation-Arousal-and-Subjective-Significance-Behavioral-and-Event-Related-Potential-Correlates-Investigated-by-Means-of-a-Modified-Emotional-Stroop-Task.pdf [33] STROTH S, KUBESCH S, DIETERLE K, et al. Physical fitness, but not acute exercise modulates event-related potential indices for executive control in healthy adolescents[J]. Brain Res, 2009, 1269: 114-124. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Markus_Kiefer/publication/24199667_Physical_fitness_but_not_acute_exercise_modulates_event-related_potential_indices_for_executive_control_in_healthy_adolescents._Brain_Res/links/0c9605243e4ff2eee8000000.pdf [34] SCUDDER M R, DROLLETTE E S, PONTIFEX M B, et al. Neuroelectric indices of goal maintenance following a single bout of physical activity[J]. Biol Psychol, 2012, 89(2): 528-531. [35] PONTIFEX M B, SALIBA B J, RAINE L B, et al. Exercise improves behavioral, neurocognitive, and scholastic performance in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder[J]. J Pediatr, 2013, 162(3): 543-551. http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC3556380/ [36] CHANG Y K, LABBAN J D, GAPIN J I, et al. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a Meta-analysis[J]. Brain Res, 2012, 1453: 87-101. http://www.onacademic.com/detail/journal_1000035033232410_aacc.html [37] NEWSOME R N, PUN C, SMITH V M, et al. Neural correlates of cognitive decline in older adults at-risk for developing MCI: evidence from the CDA and P300[J]. Cognit Neurosci, 2013, 4(3/4): 152-162. http://www.xueshufan.com/publication/2082818704 -

下载:

下载: