Dose-response relationship between emotional state and anxiety disorder among primary students

-

摘要:

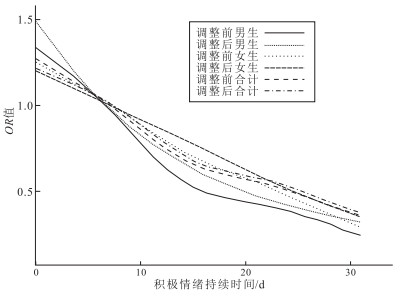

目的 探究小学生情绪体验持续时间与焦虑障碍发生关联强度的剂量-反应关系,为研究不同情绪状态水平对应的焦虑障碍发生风险提供参考。 方法 采用方便整群抽样方法,抽取上海市闵行区16所公办小学三至五年级的7 152名学生作为调查对象,采用儿童焦虑障碍自评量表及积极情感-消极情感量表进行问卷调查。 结果 小学生焦虑障碍总检出率为19.91%,其中男、女生焦虑障碍患病率分别为19.41%和20.43%。调整了性别、年级、户籍、是否为独生子女、父母婚姻状况、父母职业、父母文化程度、家庭经济水平、担任班干部、接受过体育和艺术专项培训或辅导情况及被欺凌情况后,积极情绪持续天数为7~16 d组、17~24 d组和>24 d组与焦虑障碍患病风险的发生呈负相关(OR值分别为0.53,0.36,0.37,P值均<0.05);消极情绪持续天数为0.27~0.93 d组、0.94~2 d组和>2 d组与焦虑障碍患病风险的发生呈正相关(OR值分别为1.27,3.73,7.66,P值均<0.05)。限制性立方样条分析显示,情绪状态的持续天数与焦虑障碍患病关联强度呈明显的非线性剂量-反应关系(P<0.01),即随着小学生积极情绪持续天数的增长,患焦虑障碍的风险持续降低;随着小学生消极情绪持续天数的增长,患焦虑障碍的风险持续增高。 结论 小学生情绪状态持续天数与焦虑障碍发生呈显著剂量-反应关系,促进小学生获得和维持积极情绪可作为改善小学生心理健康的重要切入点。 Abstract:Objective To explore the dose-response relationship between duration of emotional experience of primary school students and the intensity of anxiety disorders, and to understand the risk of anxiety disorders corresponding to different emotional state levels. Methods A total of 7 152 primary students from grade 3 to 5 were investigated with questionnaire survey from 16 public primary schools, by using the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorder (SCARED) and Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale. Results The prevalence of anxiety disorders was 19.91%, among which the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders in boys and girls were 19.41% and 20.43%, respectively. After adjusting for gender, grade, household register, the only child, parental marital status, parental occupation, parental educational level, family financial level, serving as a class leader, receiving special training or counseling in sports and art, and being bullied, the risk of anxiety disorder in children with positive emotions lasting for 7-16 days, 17-24 days and >24 days was lower compared to those with positive emotions lasting for less than 6 days(P<0.05); the risk of anxiety disorder in children with negative emotions lasting for 0.27-0.93 day, 0.94-2 days and >2 days was higher compared to those with negative emotions lasting less than 0.26 day(P<0.05). Restricted cubic spline analysis showed that the duration of emotional state and anxiety disorder showed a significant non-linear dose-response relationship (non-linear test, P<0.01), that is, as the number of days of positive emotions increases, the risk of anxiety disorder continues to decrease, and as the number of days of negative emotions increases, the risk of anxiety disorder continues to increase. Conclusion There is a significant dose-response relationship between the duration of the emotional state of primary school students and the prevalence of anxiety disorders. Acquirement and maintain positive emotions m be an important entry point for mental health promotion among primary school students. -

Key words:

- Emotions /

- Mental health /

- Anxiety /

- Regression analysis /

- Students

-

表 1 不同组别小学生焦虑障碍检出率比较

Table 1. Comparison of detection rates of anxiety disorders among pupils in different groups

变量 人数 焦虑人数 χ2值 P值 变量 人数 焦虑人数 χ2值 P值 性别 大专 1 627 321(19.73) 男 3 648 708(19.41) 1.18 0.28 大学本科 2 928 585(19.98) 女 3 504 716(20.43) 硕士或以上学历 951 167(17.56) 年级 母亲文化程度 三 2 487 474(19.06) 1.99 0.37 小学及以下 90 29(32.22) 17.55 < 0.01 四 2 376 477(20.08) 初中 646 154(23.84) 五 2 289 473(20.66) 高中(或中专) 1 044 209(20.02) 户籍 大专 1 784 357(20.01) 上海 4 867 966(19.85) 0.04 0.85 大学本科 3 002 564(18.79) 非上海 2 285 458(20.04) 硕士或以上学历 586 111(18.94) 独生子女 家庭经济水平 是 4 473 852(19.05) 5.58 0.02 低 712 212(29.78) 66.29 < 0.01 否 2 679 572(21.35) 中等 2 929 619(21.13) 父母婚姻状况 高 3 511 593(16.89) 在婚 6 535 1 279(19.57) 8.97 0.06 担任班干部 离婚或分居 312 67(21.47) 是 2 752 456(16.57) 31.31 < 0.01 寡居/鳏居 11 3(27.27) 否 4 400 968(22.00) 再婚 89 27(30.34) 接受过体育专项培训或辅导 不知道 205 48(23.41) 是 3 414 620(18.16) 12.55 0.02 父亲职业 否 2 565 804(21.51) 机关或企事业单位管理人员 1 444 289(20.01) 10.76 0.96 接受过艺术专项培训或辅导 有专业职称的技术人员 1 823 339(18.60) 是 4 587 850(18.53) 15.27 < 0.01 商业或服务业人员 1 409 306(21.72) 否 2 565 574(22.38) 办事或一般业务人员 769 135(17.56) 被欺凌情况 制造/生产/运输或有关人员 1 083 223(20.59) 从没有过 5 521 923(16.72) 174.17 < 0.01 未就业 136 35(25.74) 很少 1 157 328(28.35) 其他 488 97(19.88) 有时 378 130(34.39) 母亲职业 经常 65 30(46.15) 机关或企事业单位管理人员 1 238 234(18.90) 16.98 < 0.01 总是 31 13(41.94) 有专业职称的技术人员 1 156 214(18.51) 积极情绪持续天数/d 商业或服务业人员 1 489 330(22.16) 0~6 1 807 545(30.16) 222.20 < 0.01 办事或一般业务人员 1 176 220(18.71) 7~16 1 950 429(22.00) 制造/生产/运输或有关人员 722 144(19.94) 17~24 1 683 248(14.53) 未就业 939 173(18.42) >24 1 712 202(11.97) 其他 432 109(25.23) 消极情绪持续天数/d 父亲文化程度 0~0.26 1 917 143(7.46) 727.05 < 0.01 小学及以下 57 20(35.09) 16.94 < 0.01 0.27~0.93 1 710 157(9.18) 初中 519 124(23.89) 0.94~2 1 752 440(25.11) 高中(或中专) 1 070 207(19.35) >2 1 773 684(38.58) 注: ()内数字为检出率/%。 表 2 小学生情绪状态持续天数与焦虑障碍发生的Logistic回归分析(n=7 152)

Table 2. Logistic regression analysis of the duration of the emotional state and the occurrence of anxiety disorder of pupils(n=7 152)

情绪状态持续天数/d 单因素 模型a 模型b 标准误 Wald χ2值 OR值(OR值95%CI) 标准误 Wald χ2值 OR值(OR值95%CI) 标准误 Wald χ2值 OR值(OR值95%CI) 积极情绪 0~6 206.22 1.00 209.06 1.00 161.31 1.00 7~16 0.08 74.76 0.50(0.42~0.58) 0.08 76.35 0.49(0.42~0.58) 0.08 59.46 0.53(0.45~0.62) 17~24 0.09 145.31 0.33(0.28~0.40) 0.09 147.90 0.33(0.27~0.39) 0.09 118.26 0.36(0.30~0.43) >24 0.10 130.86 0.33(0.27~0.40) 0.10 132.11 0.33(0.27~0.40) 0.10 100.15 0.37(0.30~0.45) 消极情绪 0~0.26 627.52 1.00 632.16 1.00 538.42 1.00 0.27~0.93 0.23 3.66 1.26(0.99~1.61) 0.24 3.93 1.28(1.00~1.62) 0.12 3.76 1.27(1.00~1.62) 0.94~2 1.34 163.06 3.82(3.11~4.69) 1.35 165.73 3.87(3.15~4.76) 0.11 152.31 3.73(3.03~4.60) >2 2.12 426.56 8.36(6.83~10.22) 2.15 431.52 8.54(6.98~10.46) 0.11 371.55 7.66(6.23~9.42) 注: P值均<0.01。 -

[1] 郭玥, 杨光远, 徐汉明. 儿童青少年焦虑障碍的家庭关系研究[J]. 中国学校卫生, 2017, 38(12): 1912-1915. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2017.12.047GUO Y, YANG G Y, XU H M. Family relationship research on anxiety disorders in children and adolescents[J]. Chin J Sch Health, 2017, 38(12): 1912-1915. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2017.12.047 [2] COSTELLO E J, EGGER H L, ANGOLD A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity[J]. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin, 2005, 14(4): 631-648. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.06.003 [3] 周惠清, 李定国, 宋艳艳, 等. 全国城市中小学生焦虑情绪流行病学调查[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2007, 27(11): 1379-1381, 1388. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-8115.2007.11.025ZHOU H Q, LI D G, SONG Y Y, et al. Epidemiologic study of anexity state in adolescents in China[J]. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ(Med Ed), 2007, 27(11): 1379-1381, 1388. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-8115.2007.11.025 [4] 乐国安, 董颖红. 情绪的基本结构: 争论、应用及其前瞻[J]. 南开学报(哲学社会科学版), 2013(1): 140-150. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LKXB201301016.htmYUE G A, DONG Y H. On the categorical and dimensional approaches of the theories of the basic structure of emotions[J]. J Nankai(Phil Soc Sci), 2013(1): 140-150. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LKXB201301016.htm [5] OATLEY K, JOHNSON-LAIRD P N. Towards a cognitive theory of emotions[J]. Cogn Emotion, 1987, 1(1): 29-50. doi: 10.1080/02699938708408362 [6] WATSON D, TELLEGEN A. Toward a consensual structure of mood[J]. Psychol Bull, 1985, 98(2): 219. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219 [7] 左衍涛, 王登峰. 汉语情绪词自评维度[J]. 心理学动态, 1997, 5(2): 55-59. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLXD702.010.htmZUO Y T, WANG D F. The Self-evaluation dimension of Chinese emotional words[J]. Dev Psychol, 1997, 5(2): 55-59. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLXD702.010.htm [8] COHEN J N, DRYMAN M T, MORRISON A S, et al. Positive and negative affect as links between social anxiety and depression: predicting concurrent and prospective mood symptoms in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders[J]. Behav Ther, 2017, 48(6): 820-833. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.07.003 [9] 杨逸群, 陈亮, 纪林芹, 等. 母亲抑郁对青少年抑郁的影响: 亲子关系的中介作用与青少年消极情绪性的调节作用[J]. 心理发展与教育, 2017, 33(3): 368-377. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLFZ201703015.htmYANG Y Q, CHEN L, JI L Q, et al. The intergenerational transmission of maternal depression: the mediating role of mother-adolescent relationship and the moderating role of adolescents' negative affectivity[J]. Psychol Dev Educ, 2017, 33(3): 368-377. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLFZ201703015.htm [10] MCLEAN C P, FOA E B. Emotions and emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder[J]. Curr Opin Psychol, 2017, 14: 72-77. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.10.006. [11] HOFMANN S G, SAWYER A T, FANG A, et al. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders[J]. Depres Anx, 2012, 29(5): 409-416. doi: 10.1002/da.21888 [12] 林素兰, 王丹, 咸亚静, 等. 乌鲁木齐市小学生社交焦虑和抑郁现状调查[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2018, 20(8): 670-674. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-DDKZ201808016.htmLIN S L, WANG D, XIAN Y J, et al. Current status of social anxiety and depression among primary school students in Urumqi, China[J]. Chin J Contemp Pediatr, 2018, 20(8): 670-674. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-DDKZ201808016.htm [13] SHEN M, GAO J, LIANG Z, et al. Parental migration patterns and risk of depression and anxiety disorder among rural children aged 10-18 years in China: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMJ Open, 2015, 5(12): e7802. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4710829/ [14] CHORPITA B F, DALEIDEN E L. Tripartite dimensions of emotion in a child clinical sample: measurement strategies and implications for clinical utility[J]. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2002, 70(5): 1150-1160. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1150 [15] COOK J M, ORVASCHEL H, SIMCO E, et al. A test of the tripartite model of depression and anxiety in older adult psychiatric outpatients[J]. Psychol Ag, 2004, 19(3): 444-451. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.444 [16] TEACHMAN B A, SIEDLECKI K L, MAGEE J C. Aging and symptoms of anxiety and depression: structural invariance of the tripartite model[J]. Psychol Ag, 2007, 22(1): 160-170. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.160 [17] BIRMAHER B, BRENT D A, CHIAPPETTA L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders(SCARED): a replication study[J]. J Amer Academy Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 1999, 38(10): 1230-1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011 [18] LAURENT J, CATANZARO S J, THOMAS E J, et al. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: scale development and preliminary validation[J]. Psychol Assess, 1999, 3(11): 326-338. http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/pas/11/3/326/ [19] IVARSSON T, SKARPHEDINSSON G, ANDERSSON M, et al. The validity of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders Revised(SCARED-R) scale and sub-scales in swedish youth[J]. Child Psychiatry Human Dev, 2018, 49(2): 234-243. doi: 10.1007/s10578-017-0746-8 [20] ARAB A, EL KESHKY M, HADWIN J A. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders(SCARED) in a non-clinical sample of children and adolescents in Saudi Arabia[J]. Child Psychiatry Human Dev, 2016, 47(4): 554-562. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0589-0 [21] BEHRENS B, SWETLITZ C, PINE D S, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders(SCARED): informant discrepancy, measurement invariance, and test-retest reliability[J]. Child Psychiatry Human Dev, 2019, 50(3): 473-482. doi: 10.1007/s10578-018-0854-0 [22] KAAJALAAKSO K, LEMPINEN L, RISTKARI T, et al. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) among elementary school children in Finland[J]. Scandinavian J Psychol, 2020, 62(1): 34-40. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12677 [23] SEQUEIRA S L, SILK J S, WOODS W C, et al. Psychometric properties of the SCARED in a nationally representative US sample of 5-12-year-olds[J]. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 2020, 49(6): 761-772. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2019.1614001 [24] 沈晓霜, 李欣, 闫军伟, 等. 新型冠状病毒肺炎流行期间安徽省中小学生的焦虑情绪[J]. 中国心理卫生杂志, 2020, 34(8): 715-719. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZXWS202008017.htmSHEN X S, LI X, YAN J W, et al. Anxiety of primary and middle school students in Anhui province during the COVID-19 epidemic[J]. J Chin Mental Health, 2020, 34(8): 715-719. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZXWS202008017.htm [25] 李少闻, 王悦, 杨媛媛, 等. 新型冠状病毒肺炎流行期间居家隔离儿童青少年焦虑性情绪障碍的影响因素分析[J]. 中国儿童保健杂志, 2020, 28(4): 407-410. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ERTO202004014.htmLI S W, WANG Y, YANG Y Y, et al. Investigation on the influencing factors for anxiety related emotional disorders of children and adolescents with home quarantine during the prevalence of coronavirus disease 2019[J]. Chin J Child Health Care, 2020, 28(4): 407-410. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ERTO202004014.htm [26] 徐学兵, 王瑞, 何海燕, 等. 宁夏灵武市某小学学生情绪问题状况的调查[J]. 宁夏医学杂志, 2015, 37(12): 1223-1225. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-NXYX201512082.htmXU X B, WANG R, HE H Y, et al. Investigation of emotional problems among primary school students in Lingwu City, Ningxia[J]. Ningxia Med J, 2015, 37(12): 1223-1225. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-NXYX201512082.htm [27] 顾红亮, 范娟, 杨慧琳, 等. 上海市浦东新区儿童焦虑症状现状调查及对生活质量的影响(英文)[J]. 上海精神医学, 2011, 23(3): 154-160. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2011.03.004GU H L, FAN J, YANG H L, et al. Anxiety symptoms and quality of life among children living in the Pudong district of Shanghai: a cross-sectional study[J]. Shanghai Ach Psych, 2011, 23(3): 154-160. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2011.03.004 [28] LIAO H, PAN M, LI W, et al. Latent profile analysis of anxiety disorder among left-behind children in rural southern China: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMJ Open, 2019, 9(6): e29331. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/6/e029331.full [29] 邢小莉, 赵俊峰, 赵国祥. 神经及内分泌系统对社会支持缓冲应激的调节机制[J]. 心理科学进展, 2016, 24(4): 517-524. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLXD201604006.htmXING X L, ZHAO J F, ZHAO G X. Role of social support in buffering effects of stress on neural and endocrine systems[J]. Adv Psychol Sci, 2016, 24(4): 517-524. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLXD201604006.htm [30] GROSS J J, JAZAIERI H. Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology[J]. Clin Psychol Sci, 2014, 2(4): 387-401. doi: 10.1177/2167702614536164 [31] TURNER A I, SMYTH N, HALL S J, et al. Psychological stress reactivity and future health and disease outcomes: a systematic review of prospective evidence[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2020, 114: 104599. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104599. [32] KLEIN HOFMEIJER-SEVINK M, BATELAAN N M, van MEGEN H J G M, et al. Clinical relevance of comorbidity in anxiety disorders: a report from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety(NESDA)[J]. J Affect Dis, 2012, 137(1/3): 106-112. http://labs.europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22240085 [33] SALA R, GOLDSTEIN B I, MORCILLO C, et al. Course of comorbid anxiety disorders among adults with bipolar disorder in the U.S. population[J]. J Psychiatr Res, 2012, 46(7): 865-872. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.024 [34] LAMERS F, van OPPEN P, COMIJS H C, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety(NESDA)[J]. J Clin Psychiatry, 2011, 72(3): 341-348. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu [35] SAUNDERS E F H, FITZGERALD K D, ZHANG P, et al. Clinical features of bipolar disorder comorbid with anxiety disorders differ between men and women[J]. Depres Anx, 2012, 29(8): 739-746. doi: 10.1002/da.21932 [36] FISCHER A H, KRET M E, BROEKENS J. Gender differences in emotion perception and self-reported emotional intelligence: a test of the emotion sensitivity hypothesis[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(1): e190712. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29370198 [37] 颜志强, 苏彦捷. 共情的性别差异: 来自元分析的证据[J]. 心理发展与教育, 2018, 34(2): 129-136. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLFZ201802001.htmYAN Z Q, SU Y J. Gender difference in empathy: the evidence from meta-analysis[J]. Psychol Dev Educ, 2018, 34(2): 129-136. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLFZ201802001.htm [38] BHASKARAN K, DOS-SANTOS-SILVA I, LEON D A, et al. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3.6 million adults in the UK[J]. Lancet Diab Endoc, 2018, 6(12): 944-953. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30288-2 -

下载:

下载: